Generative AI has taken the internet by storm with its ability to spit out images and blobs of text based on user queries. Despite widespread hysteria that artificial intelligence will make most of our jobs irrelevant, it could actually streamline the workflow for plenty of professions—including music production.

We chose a couple of our favorite tools for simplifying music production and put them to the test, demonstrating a real-world scenario in which this technology could be used for good instead of evil. It’s time we embrace this new technology as a helping hand rather than disavow it as a doomsday device, and we hope this guide will help you get your feet wet.

What’s The Deal With AI Music Generators?

It’s important to note that some of these programs can generate music—but we’re still far from being able to push a button to churn out a one-hit-wonder. The AI music generators we tested are legitimate tools, unlike the voice changers you may have seen that can make anyone sound like Drake. (The New York Times recently chronicled an AI Drake hit that briefly went viral before being stripped from streaming services, and spoiler alert, he was not happy.)

Messing around with Riffusion, it didn’t take long to realize that none of the music is necessarily Spotify ready out of the box—I guess it also helps to have even a lick of musical talent. However, this basic idea made me realize that these programs are helpful for ideation in song creation, and not necessarily “cheating” and doing the musician’s whole job. Most of these tools are much simpler to use than ChatGPT, Midjourney, and some of the other models we’ve written about previously.

✅ How Do AI Music Generators Work? Much like AI image generators and text-based AI tools, AI music generators rely on deep learning—a machine learning method in which computers process data in a way that mimics the human mind—to create an output. Specifically, the software must be fed vast amounts of training data (here, examples of music) and process it. But if you only teach the system with the greatest hits from the Beatles, for instance, any melody that the AI music generator would produce after that training period would sound a whole hell of a lot like ... the Beatles. That’s why a huge library of training data, from varied sources, is key to this process.

Riffusion

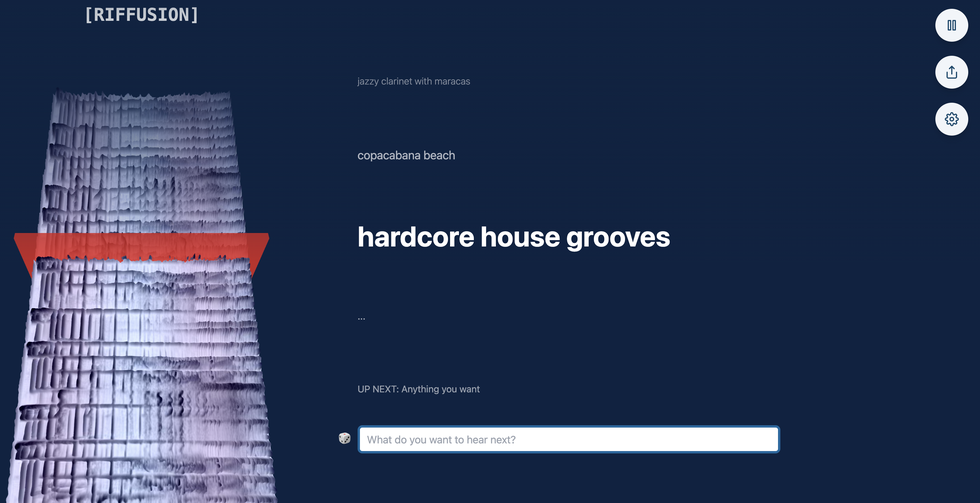

This super lightweight web app was one of the first AI music models I began playing around with. Using Stable Diffusion—yes, the same platform that creates images—Riffusion is able to create an image that’s then synthesized to create “music.” I use the quotations there sparingly as many of the ideas it spits out are not only low-fidelity but also quite basic. However, it can absolutely provide a musician with a cool riff or beat that they could use in their work.

The white slab that you see to the left of the screen is the image Riffusion synthesizes. The app analyzes the peaks and valleys, and proceeds to translate the physical form into music the same way a record player interprets sound from the ridges on vinyl. Along with the prompts (see the photo above for an example), I also have control over melodic patterns, creativity, tempo, and that’s about it.

Nothing special, but it’s more than enough to get the creative juices flowing.

ChatGPT

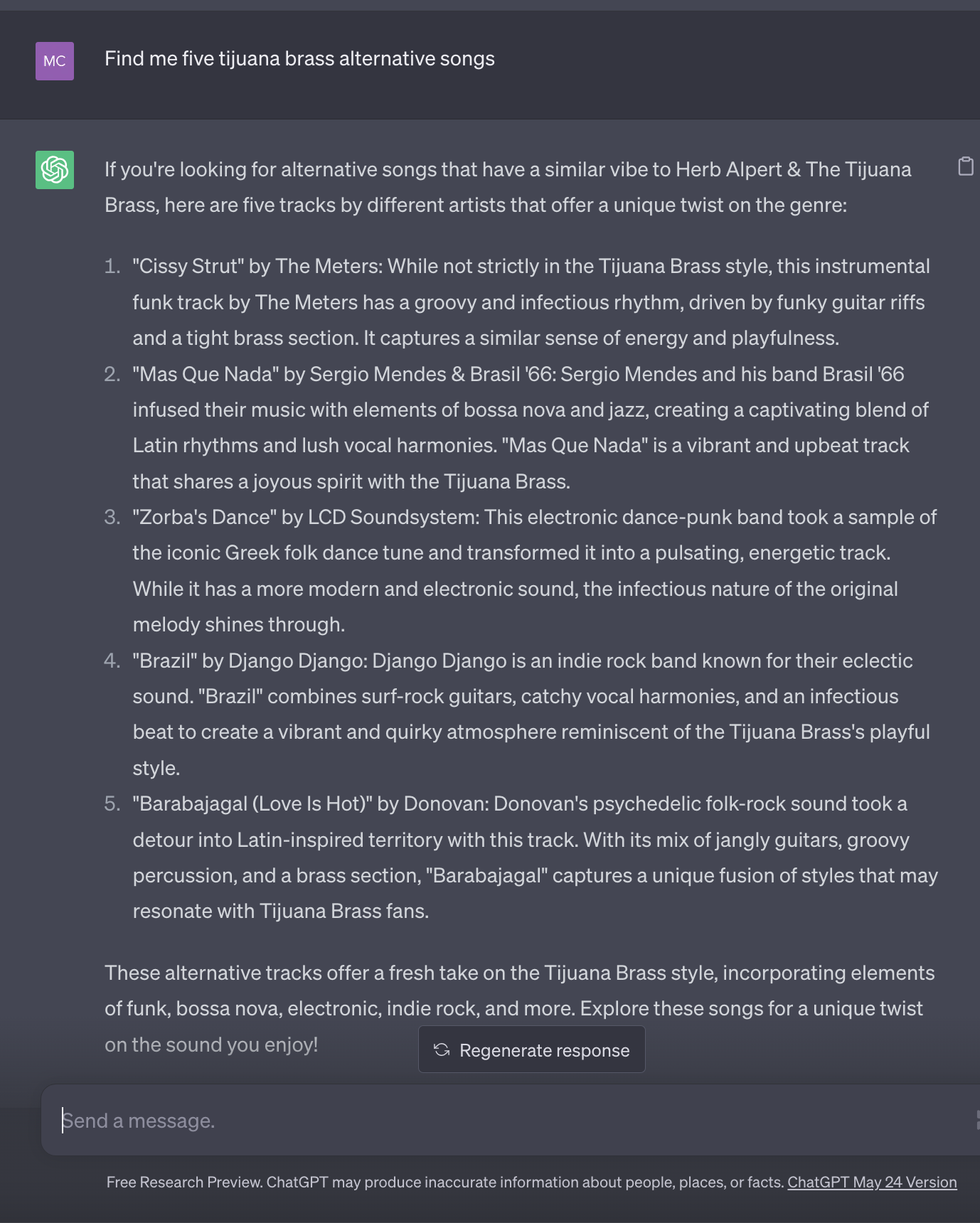

Despite some of the sillier things I’ve asked ChatGPT to do, it didn’t take me long to realize that it could actually be another incredibly useful tool for musicians looking to find samples—and even lyrics. Sure, most of its training data is from 2021 and earlier, but this isn’t a big issue as there’s a plethora of great tunes to choose from that predate even the 21st century. As you’ll see below, I asked it for five samples with similar vibes to Tijuana Brass.

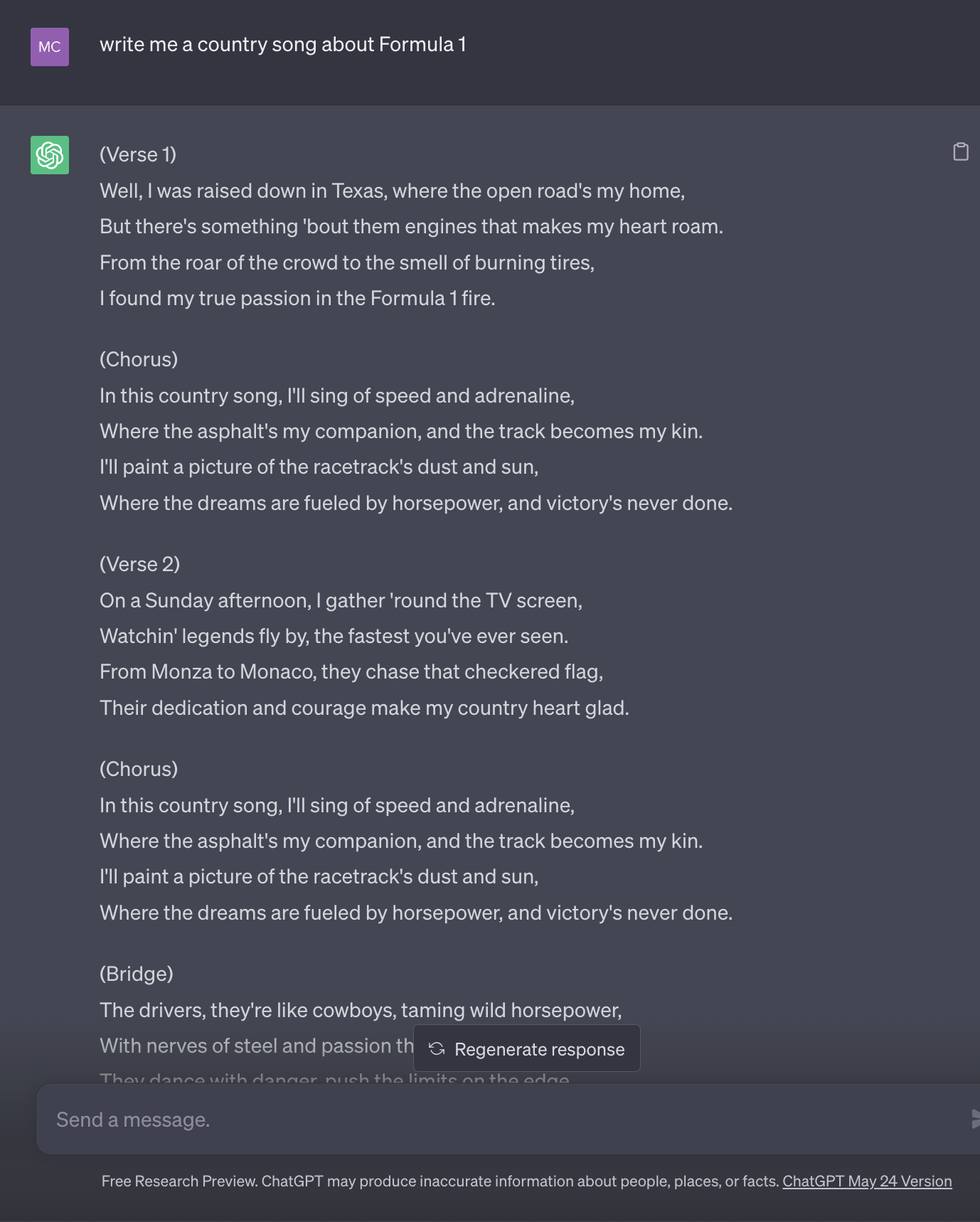

Along with finding samples, it’s also a great tool for writing lyrics. They’re not perfect, but with a little human intervention, the lyrics below are a great springboard for writing a country song about Formula 1.

Samplette.io

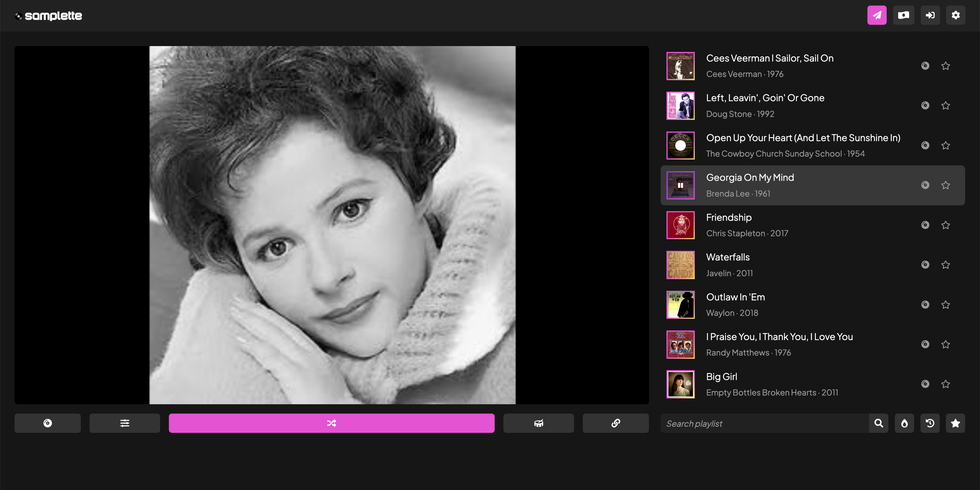

While ChatGPT is a great starting point for finding new music, Samplette IO gives you more control over the results. Instead of aimlessly sifting through YouTube, this app gives you eight filters to tune your search results—genre, style, country, key, tempo, vocality, views, and year—and find exactly what you want. It also includes a keyword section to further narrow down your findings.

Samplette is also a super useful tool for finding new music. I’ve also never had to skip through ads while listening to music—make of that information what you will. Don’t tell Spotify, but I’ve found Samplette’s algorithm way better at finding fresh music. I generally just leave it on shuffle while I’m working.

Isn’t This Copyright Infringement?

AI anything becomes considerably more complex regarding intellectual property, especially when it comes to music. (This article from The Verge provides deeper context into the seemingly endless gray areas of musical copyright, and how we should proceed into an era where AI-assisted music generation is likely here to stay.)

Generative AI models—including music generators—must be trained with existing material. This is often conflated with stealing content, but there’s really no other way for these programs to generate music. It’s not dissimilar to how humans wouldn’t be able to make music without hearing it first. You’re not necessarily stealing it, but are instead riffing from other works.

It’s comparable to how samples—notes and melodies taken from other songs to spruce up someone else’s work—play out in the music industry. Copyright laws regarding samples sound incredibly simple, given that artists need explicit permission to use someone else’s work.

However, this is actually where things get incredibly complicated. Can you copyright a chord progression? How similar does one song have to be to raise a red flag? Who decides how similar two works actually are? Earlier this year, for instance, Ed Sheeran was cleared of any wrongdoing after claims that his original song, “Thinking Out Loud,” strayed too close to Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On.”

In the case of AI music, the situation is ongoing. That being said, the use of copyrighted music to train these models is currently the biggest rock in most musicians’ shoes.

Other Applications

While AI music is mostly a gimmick at the moment, we reckon that it could soon revolutionize the production process for small filmmakers—among many others use cases. These collectives often have very little budget to spare for creating a score to complement their films.

In my couple of weeks with these programs, it’s clear that AI music-making has a very long way to go before Hollywood’s score composers have to start worrying about their job security. AI tools can give you a fairly good product, but most of the programs I used gave me limited control of the finished product; you’re unable to change individual notes and chord progressions, and are instead able to tweak the mood, dynamics, and lyrics.

Going Forward

Much like the other AI tools that we’ve written about, music generators aren’t anything to panic about. They’re great for messing around, and can give you good results, but they still can’t compete with the creativity and intricacies of a human being composing a song or playing an instrument. I do wonder if artists and composers could start using these tools for inspiration in the not-so-distant future. Let us know your thoughts below.

Matt Crisara is a native Austinite who has an unbridled passion for cars and motorsports, both foreign and domestic. He was previously a contributing writer for Motor1 following internships at Circuit Of The Americas F1 Track and Speed City, an Austin radio broadcaster focused on the world of motor racing. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Arizona School of Journalism, where he raced mountain bikes with the University Club Team. When he isn’t working, he enjoys sim-racing, FPV drones, and the great outdoors.